|

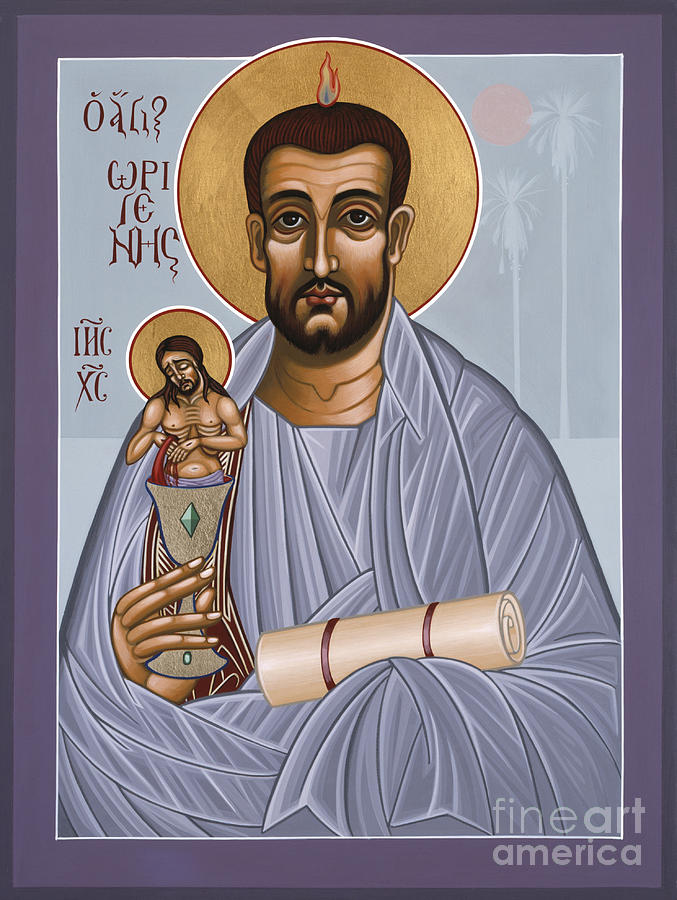

| Origen the Theologian |

Pope Fabian reigned from 236 AD to 250 AD as captain of the Bark of Peter, while a relative calm descend on the Church. He tended to the Church with a missionary spirit, appointing 7 missionary bishops to go throughout France, bringing them the Good News. Most of them were martyred, however not by Rome this time, but by pagan barbarians.

Origen of Alexandria. (185 AD – 253 AD) became famous for a debate he had with a pagan philosopher, at this time. Christianity had grown to the point that pagan philosophers felt the need to address this movement.

Origen is still considered to be one of the greatest Bible scholars of all time. He was a teacher at, The Catechetical School of Alexandria, which was the oldest catechetical school in the world. It functioned similarly to a college of today. St. Jerome records that The Catechetical School of Alexandria was founded by St. Mark – the writer of the second Gospel.

Under the leadership of the scholar Pantaenus, the school of Alexandria became an important institution of religious learning, where students were taught by scholars such as Athenagoras, Clement of Alexandria , Didymus, and the great Origen, who was considered the father of theology, and a leader in the field of commentary and comparative Biblical studies. Many scholars visited the school of Alexandria to exchange ideas and to communicate directly with its scholars.

The scope of this school was not limited to theological subjects. Apart from subjects like theology, Christian philosophy and the Bible; there was science, mathematics, Greek & Roman literature, logic and the arts were also taught. The question-and-answer method of commentary began there, and, 15 centuries before Braille, blind students at the school were using wood-carving techniques to read and write.

Born in 185 AD, Origen was seventeen when a bloody persecution of the Church of Alexandria broke out. He and his father loved each other very much. Origen’s father, Leonides, saw the genius of his son, and made the effort to get him an excellent classical education, also he instilled a love for virtue and his Christian Faith. His father was arrested and martyred during this persecution, and so inspired by his father’s example; he sought to be also martyred by joining a protest. His mother would not allow this, legend has it that she hid his clothes, so he could not participate.

Deterred by his mother, he wrote an enthusiastic letter to his father encouraging him to persevere courageously. When Leonides, his father, had won the martyr's crown, authorities seized the family's fortune– they were wealthy.

These hard times showed the heroic virtue of this young man. He sought a way to support his mother, and his six younger brothers. He accomplished this by becoming a teacher, selling manuscripts, and by the generous aid of a patroness, who admired his talents.

He soon found his way to be a teacher at the Catechetical School, on the withdrawal of Clement of Alexandria. Clement was also a great teacher and head of the Catechetical School. He worked to combine the best of pagan Greek and Roman learning with the Christian faith. In the following year Origen was confirmed in Clement's office by the patriarch Demetrius (Eusebius, Church History VI.2; St. Jerome, "De viris illust.", liv). The reputation of the school was so good that pagans frequently attended it.

Origen didn’t rest on his reputation, but deepened his knowledge of pagan philosophers particularly Plato and the Stoics, even learning Hebrew, and communicated frequently with learned Jews who helped him to solve his Biblical difficulties.

As Origen’s fame increased he was invited to visit many countries, traveling for about a five year period. He was invited to preach in Caesarea and Jerusalem by Bishop Theoctistus and Bishop Alexander of Jerusalem, who invited him to preach, even though he was still a layman. (All this is covered in Eusebius, Church History book 6.).

This is where trouble began for Origen. The Bishop of Caesarea, Theoctistus, saw it as a tragedy that Origen was not ordained as a priest. So Theoctistus took the liberty to rectify the situation, and ordained him. This came as a shock and insult to the Patriarch in Alexandria, Egypt. Origen was a teacher at his school in Egypt and shouldn’t be ordained by a foreigner bishop. On Origen’s return, he found the greetings very cold, and noticed that his Patriarch bishop, Demetrius, was not as kind as when he left. Origen, saw the handwriting on the wall – he was not welcome. He decided to return to Caesarea in Palestine, where he started his own school.

In retaliation, Patriarch Demetrius of Alexanderia in Egypt held two councils to condemn Origen. Demetrius condemned Origen for insubordination and accused him of having castrated himself and of having taught that even Satan would eventually attain salvation, an accusation which Origen vehemently denied. (cf. McGuckin, 2004, "The Life of Origen)

One council was to banish him from the dioceses, and the other was to revoke his priesthood. St. Jerome declares expressly that he was not condemned on a point of doctrine but on discipline. And it is questionable, if the revoking of his ordination was valid, nor even his banishment. Unfortunately power corrupts and egos can seek retaliation, even among the authorities in the Church, such as this bishop. The details of the whole affair were recorded by Eusebius in the lost second book of the "Apology for Origen," which we only have second hand knowledge from.

Origen had a successful school in Caesarea, attracting many students, because of his fame as a teacher. He visited religious sites and limitedly traveled, but mainly he dedicated his time to studying scripture, writing his commentaries, and preaching. He also found time to refute heretics who denied the Resurrection. During the persecution of 235-37 AD his bishop of Caesarea insisted he remain hidden, with the bishop's help. As a priest now, he needed to be obedient to his bishop. He survived that persecution, but was arrested in the next persecution, in 250 AD. Origien was arrested and tortured. He was still alive in prison at the death of Emperor Decius (251 AD), but only barely. He soon died after, probably, from the tortures he endured at the age of 69 –253 AD or 254 AD. (cf.Eusebius, Church History Book 7)

For a long time his sepulcher, behind the high-altar of the cathedral of Tyr, was visited by pilgrims. Today, nothing remains of this cathedral except a mass of ruins, the exact location of his tomb is unknown.

Origen’s Work and Legacy

We need to address this great man’s work and legacy. St. Jerome was an avid admirer of his, but later turned away from him. Even today some theologians are attracted by Origen’s writings, since they are very profound and well studied. But his teachings and methods may contain some serious errors. Whether Origen was guilty or not of heresy is a controversy we may never have resolved in this life.

A few of the major issues that surfaced many years after his death was: universalism– all will be saved even the demons, and Satan himself; also the preexistence of souls– souls are not created with the body at conception, but existed in a nether world-- in pre-existence.

Finally his allegorical method has been his most enduring legacy– overemphasizing the symbolic meaning of scripture, over the literal meaning of scripture. St. Jerome, who became an enemy of Origen, established the Catholic method of interpreting scripture– first we must seek the literal, before the allegorical.

This is such a complicated controversy we will repost from Wikipedia which explains it well, with slight corrections:

Before the Crises

Origen is often seen as the first major Christian theologian.Though his orthodoxy had been questioned in Alexandria while he was alive, after Origen's death Pope Dionysius of Alexandria became one of the foremost proponents of Origen's theology. Every Christian theologian who came after him was influenced by his theology, whether directly or indirectly.

Origen's contributions to theology were so vast and complex, however, that his followers frequently emphasized drastically different parts of his teachings to the expense of other parts. Dionysius emphasized Origen's subordinationist views, which led him to deny the unity of the Trinity, causing controversy throughout North Africa. At the same time, Origen's other disciple Theognostus of Alexandria taught that the Father and the Son were "of one substance".

For centuries after his death, Origen was regarded as the bastion of orthodoxy, and his philosophy practically defined Eastern Christianity. Origen was revered as one of the greatest of all Christian teachers; he was especially beloved by monks, who saw themselves as continuing in Origen's ascetic legacy.

As time progressed, however, Origen became criticized under the standard of orthodoxy in later eras, rather than the standards of his own lifetime. In the early fourth century, the Christian writer Methodius of Olympus criticized some of Origen's more speculative arguments but otherwise agreed with Origen on all other points of theology. Peter of Antioch and Eustathius of Antioch criticized Origen as heretical.

Both orthodox and heterodox theologians claimed to be following in the tradition Origen had established. Athanasius of Alexandria, the most prominent supporter of the Holy Trinity at the First Council of Nicaea, was deeply influenced by Origen, and so were Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus (the so-called "Cappadocian Fathers"). At the same time, Origen deeply influenced Arius of Alexandria and later followers of Arianism. Although the extent of the relationship between the two is debated, in antiquity, many orthodox Christians believed that Origen was the true and ultimate source of the Arian heresy.

First Origenist Crisis

St. Jerome in His Study (1480), by Domenico Ghirlandaio. Although initially a student of Origen's teachings, Jerome turned against him during the First Origenist Crisis. He nonetheless remained influenced by Origen's teachings for his entire life.

The First Origenist Crisis began in the late fourth century, coinciding with the beginning of monasticism in Palestine. The first stirring of the controversy came from the Cyprian bishop Epiphanius of Salamis, who was determined to root out all heresies and refute them.

Epiphanius attacked Origen in his anti-heretical treatises Ancoratus and Panarion, compiling a list of teachings Origen had espoused that Epiphanius regarded as heretical. Epiphanius's treatises portray Origen as an originally orthodox Christian who had been corrupted and turned into a heretic by the evils of "Greek education". Epiphanius particularly objected to Origen's subordinationism, his "excessive" use of allegorical hermeneutic, and his habit of proposing ideas about the Bible "speculatively, as exercises" rather than "dogmatically".

Epiphanius asked John, the bishop of Jerusalem, to condemn Origen as a heretic. John refused on the grounds that a person could not be retroactively condemned as a heretic after that person had already died. In 393, a monk named Atarbius advanced a petition to have Origen and his writings censured. Tyrannius Rufinus, a priest at the monastery on the Mount of Olives who had been ordained by John of Jerusalem and was a longtime admirer of Origen, rejected the petition outright. Rufinus's close friend and associate Jerome, who had also studied Origen, however, came to agree with the petition. Around the same time, John Cassian, an Eastern monk, introduced Origen's teachings to the West.

In 394, Epiphanius wrote to John of Jerusalem, again asking for Origen to be condemned, insisting that Origen's writings denigrated human sexual reproduction and accusing him of having been an Encratite. John once again denied this request. By 395, Jerome had allied himself with the anti-Origenists and begged John of Jerusalem to condemn Origen, a plea which John once again refused. Epiphanius launched a campaign against John, openly preaching that John was an Origenist deviant. He successfully persuaded Jerome to break communion with John and ordained Jerome's brother Paulinianus as a priest in defiance of John's authority.

In 397 AD, Rufinus published a Latin translation of Origen's On First Principles. Rufinus was convinced that Origen's original treatise had been interpolated by heretics and that these interpolations were the source of the heterodox teachings found in it. He therefore heavily modified Origen's text, omitting and altering any parts which disagreed with contemporary Christian orthodoxy.

In the introduction to this translation, Rufinus mentioned that Jerome had studied under Origen's disciple Didymus the Blind, implying that Jerome was a follower of Origen. Jerome was so incensed by this that he resolved to produce his own Latin translation of On the First Principles, in which he promised to translate every word exactly as it was written and lay bare Origen's heresies to the whole world. Jerome's translation has been lost in its entirety.

In 399, the Origenist crisis reached Egypt. Pope Theophilus of Alexandria was sympathetic to the supporters of Origen and the church historian, Sozomen, records that he had preached the Origenist teaching that God was incorporeal. In his Festal Letter of 399, he denounced those who believed that God had a literal, human-like body, calling them illiterate "simple ones". A large mob of Alexandrian monks who regarded God as anthropomorphic rioted in the streets. According to the church historian Socrates Scholasticus, in order to prevent a riot, Theophilus made a sudden about-face and began denouncing Origen.

In 400, Theophilus summoned a council in Alexandria, which condemned Origen and all his followers as heretics for having taught that God was incorporeal, which they decreed contradicted the only true and orthodox position, which was that God had a literal, physical body resembling that of a human.

But there was confusion in this point. Because God as a whole is Spirit the second person of the Trinity did become man. But when we speak of God as a whole we are usually referring to Him as a Spirit. The language to describe this was lacking in Origen's day.

Theophilus labeled Origen as the "hydra of all heresies" and persuaded Pope Anastasius I to sign the letter of the council, which primarily denounced the teachings of the Nitrian monks associated with Evagrius Ponticus.

In 402, Theophilus expelled Origenist monks from Egyptian monasteries and banished the four monks known as the "Tall Brothers", who were leaders of the Nitrian community. John Chrysostom, the patriarch of Constantinople, granted the Tall Brothers asylum, a fact which Theophilus used to orchestrate John's condemnation and removal from his position at the Synod of the Oak in July 403. Once John Chrysostom had been deposed, Theophilus restored normal relations with the Origenist monks in Egypt and the first Origenist crisis came to an end.

Second Origenist Crisis

Emperor Justinian I, shown here in a contemporary mosaic portrait from Ravenna, denounced Origen as a heretic and ordered all of his writings to be burned.

The Second Origenist Crisis occurred in the sixth century, during the height of Byzantine monasticism. Although the Second Origenist Crisis is not nearly as well documented as the first, it seems to have primarily concerned the teachings of Origen's later followers, rather than what Origen had written. Origen's disciple Evagrius Ponticus had advocated contemplative, noetic prayer, but other monastic communities prioritized asceticism in prayer, emphasizing fasting, labors, and vigils.

Some Origenist monks in Palestine, referred to by their enemies as "Isochristoi" (meaning "those who would assume equality with Christ"), emphasized Origen's teaching of the pre-existence of souls and held that all souls were originally equal to Christ's and would become equal again at the end of time.

Another faction of Origenists in the same region instead insisted that Christ was the "leader of many brethren", as the first-created being. This faction was more moderate, and they were referred to by their opponents as "Protoktistoi" ("first createds"). Both factions accused the other of heresy, and other Christians accused both of them of heresy.

The Protoktistoi appealed to the Emperor Justinian I to condemn the Isochristoi of heresy through Pelagius, the papal apocrisarius. In 543, Pelagius presented Justinian with documents, including a letter denouncing Origen written by Patriarch Mennas of Constantinople, along with excerpts from Origen's On First Principles and several anathemata against Origen.

A domestic synod convened to address the issue concluded that the Isochristoi's teachings were heretical and, seeing Origen as the ultimate culprit behind the heresy, denounced Origen as a heretic as well. Emperor Justinian ordered for all of Origen's writings to be burned. In the west, the Decretum Gelasianum, which was written sometime between 519 and 553, listed Origen as an author whose writings were to be categorically banned.

In 553, during the early days of the Second Council of Constantinople (the Fifth Ecumenical Council), when Pope Vigilius was still refusing to take part in it despite Justinian holding him hostage, the bishops at the council ratified an open letter which condemned Origen as the leader of the Isochristoi.

The letter was not part of the official acts of the council, and it more or less repeated the edict issued by the Synod of Constantinople in 543. It cites objectionable writings attributed to Origen, but all the writings referred to in it were actually written by Evagrius Ponticus. After the council officially opened, but while Pope Vigillius was still refusing to take part, Justinian presented the bishops with the problem of a text known as The Three Chapters, which attacked the Antiochene Christology.

The bishops drew up a list of anathemata against the heretical teachings contained within The Three Chapters and those associated with them. In the official text of the eleventh anathema, Origen is condemned as a Christological heretic, but Origen's name does not appear at all in the Homonoia, the first draft of the anathemata issued by the imperial chancery, nor does it appear in the version of the conciliar proceedings that was eventually signed by Pope Vigillius, a long time afterwards.

These discrepancies may indicate that Origen's name may have been retrospectively inserted into the text after the council.

Some authorities believe these anathemata belong to an earlier local synod. Even if Origen's name did appear in the original text of the anathema, the teachings attributed to Origen that are condemned in the anathema were actually the ideas of later Origenists, which had very little grounding in anything Origen had actually written.

In fact, Popes Vigilius, Pelagius I, Pelagius II, and Gregory the Great were only aware that the Fifth Council specifically dealt with The Three Chapters and make no mention of Origenism or universalism, nor spoke as if they knew of its condemnation—even though Gregory the Great was opposed to universalism.

After the Anathemas

If orthodoxy were a matter of intention, no theologian could be more orthodox than Origen, none more devoted to the cause of the Christian faith.

— Henry Chadwick, scholar of early Christianity, in the Encyclopædia Britannica

As a direct result of the numerous condemnations of his work, only a tiny fraction of Origen's voluminous writings have survived.

Nonetheless, these writings still amount to a massive number of Greek and Latin texts, very few of which have yet been translated into English.

Many more writings have survived in fragments through quotations from later Church Fathers. Even in the late 14th Century, Francesc Eiximenis in his Llibre de les dones, produced otherwise unknown quotations from Origen, which may be evidence of other works surviving into the Late Medieval period.

It is likely that the writings containing Origen's most unusual and speculative ideas have been lost to time, making it nearly impossible to determine whether Origen actually held the heretical views which the anathemas against him ascribed to him.

Nonetheless, in spite of the decrees against Origen, the church remained enamored of him and he remained a central figure of Christian theology throughout the first millennium. He continued to be revered as the founder of Biblical exegesis, and anyone in the first millennium who took the interpretation of the scriptures seriously would have had knowledge of Origen's teachings.

No comments:

Post a Comment